WARREN COUNTY

Page 740

WARREN COUNTY was formed from Hamilton, May 1, 1803, and named in honor of Gen. Joseph Warren, who fell at the battle of Bunker Hill.

The surface is generally undulating, but Harlan township embraces a part of an extensive region formerly known as “The Swamps,” now drained and cultivated. The greater portion of the county is drained by the Little Miami river. The soil is nearly all productive, much of it being famed for its wonderful strength and fertility.

Area, about 400 square miles. In 1887 the acres cultivated were 136,739; in pasture, 32,696; woodland, 30,282; lying waste, 5,724; produced in wheat, 394,588 bushels; rye, 715; buckwheat, 193; oats, 304,601; barley, 1,306; corn, 1,453,744; broom corn, 7,550 lbs. brush; meadow hay, 18,042 tons; clover hay, 2,871; flaxseed, 64 bushels; potatoes, 25,599; tobacco, 246,863 lbs.; butter, 524,454; sorghum, 925 gallons; maple syrup, 5,689; honey, 1,946 lbs.; eggs, 373,189 dozen; grapes, 9,400 lbs.; wine, 50 gallons; sweet potatoes, 3,886 bushels; apples, 3,940; peaches, 70; pears, 1,682; wool, 83,761 lbs.; milch cows owned, 5,587. School census, 1888, 7,611; teachers, 168. Miles of railroad track, 100.

|

Township And Census |

1840 |

1880 |

Township And Census |

1840 |

1880 |

|

Clear Creek, |

2,821 |

2,782 |

Salem, |

2,955 |

2,052 |

|

Deerfield, |

1,875 |

2,011 |

Turtle Creek, |

4,951 |

5,799 |

|

Franklin, |

2,455 |

4,148 |

Union, |

1,617 |

1,110 |

|

Hamilton, |

1,178 |

2,523 |

Washington, |

1,306 |

1,390 |

|

Harlan, |

|

2,242 |

Wayne, |

3,392 |

2,904 |

|

Massie, |

|

1,431 |

|

|

|

Population of Warren in 1820 was 17,838; 1830, 21,474; 1840, 23,073; 1860, 26,902; 1880, 28,392; of whom 23,256 were born in Ohio; 648 Virginia; 573 Pennsylvania; 539 Kentucky; 364 Indiana; 188 New York; 574 German Empire; 520 Ireland; 184 England and Wales; 32 Scotland; 24 France; 24 British America, and 4 Norway and Sweden.

Census 1890, 25,468.

On September 21, 1795, William BEDLE, from New Jersey, set out from one of the settlements near Cincinnati with a wagon, tools and provisions, to make a new settlement in the Third or Military Range. This was about one month after the fact had become known that Wayne had made a treaty of peace with the Indians. He travelled with a surveying party under Capt. John Dunlap, following Harmar’s trace to his lands, where he left the party and built a block-house as a protection against the Indians, who might not respect the treaty of peace.

Bedle’s Station was a well-known place in the early history of the county, and was five miles west of Lebanon and nearly two miles south of Union village. Here several families lived in much simplicity, the clothing of the children being made chiefly out of dressed deerskin, some of the larger girls being clad in buck-skin petticoats and short gowns. Bedle’s Station has generally been regarded as the first settlement in the county. About the time of its settlement, however, or not long after, William MOUNTS and five others established Mounts’ Station, on a broad and fertile bottom on the south side of the Little Miami, about three miles below the mouth of Todd’s Fork, building their cabins in a circle around a spring as a protection against the Indians.

Deerfield, now South Lebanon, is probably the oldest town in the county. Its proprietors gave a number of lots to those who would erect houses on them and

Page 741

become residents of the place. On January 25, 1796, the proprietors advertised in the Centinel of the Northwest Territory that all the lots they proposed to donate had been taken, and that twenty-five houses and cabins had been erected. Benjamin STITES, Sr., Benjamin STITES, Jr., and John Stites GANO were the proprietors. The senior STITES owned nearly ten thousand acres between Lebanon and Deerfield. Andrew LYTLE, Nathan KELLY and Gen. David SUTTON were among the early settlers at Deerfield. The pioneer and soldier, Capt. Ephraim KIBBEY, died here in 1809, aged 55 years.

In the spring of 1796 settlements were made in various parts of the county. The settlements at Deerfield, Franklin and the vicinities of Lebanon and Waynesville, all date from the spring of 1796. It is probable that a few cabins were erected at Deerfield and Franklin in the autumn of 1,795, but it is not probable that any families were settled at either place until the next spring.

Among the earliest white men who made their homes in the county were those who settled on the forfeitures in Deerfield township. They were poor men, wholly destitute of means to purchase land, and were willing to brave dangers from savage foes, and to endure the privations of a lonely life in the wilderness to receive gratuitously the tract of 106⅔ acres forfeited by each purchaser of a section of land who did not commence improvements within two years after the date of his purchase. In a large number of the sections below the third range there was a forfeited one-sixth part, and a number of hardy adventurers had established themselves on the northeast corner of the section. Some of these adventurers were single men, living solitary and alone in little huts, and supporting themselves chiefly with their rifles. Others had their families with them at an early period.

THE PERILOUS ADVENTURE OF CAPT. BENHAM.

Capt. Robert BENHAM, the subject of one of the most romantic stories in the history of the Ohio valley, died on a farm about a mile southwest of Lebanon, in 1809, aged 59 years. He is said to have built, in 1789, the first hewed log-house in Cincinnati, and established a ferry at Cincinnati over the Ohio, February 18, 1792. He was a member of the first Territorial Legislature, and of the first board of county commissioners of Warren county. He was a native of Pennsylvania and a man of great muscular strength and activity. He was one of a party of seventy men who were attacked by Indians near the Ohio, opposite Cincinnati, in the war of the Revolution, the circumstances of which here follow from a published source.

In the autumn of 1779 a number of

keel boats were

ascending the Ohio under the command of Maj. Rodgers and had advanced

as far as

the mouth of Licking without accident. Here, however, they observed a few Indians standing up on the

southern

extremity of a sandbar, while a canoe, rowed by three others, was in

the act of putting off from the Kentucky shore, as if for the

purpose of taking them aboard.

Rodgers immediately ordered the boats to be made fast on the Kentucky

shore,

while the crew, to the number of seventy men, well armed, cautiously

advanced in such a manner as to encircle the spot where

the enemy had been seen to land.

Only

five or six Indians had been seen, and no one dreamed of

encountering

more than fifteen or twenty

enemies. When Rodgers,

however had, as he supposed,

completely surrounded the enemy, and was preparing to rush upon them

from

several quarters at once, he was thunderstruck at beholding several

hundred

savages suddenly spring up in front, rear, and

upon

both flanks. They instantly

poured in a

close discharge of rifles, and then throwing down their guns, fell upon

the

survivors with the tomahawk. The panic was complete, and the slaughter prodigious. Maj. Rodgers, together with

forty-five others

of his men, were quickly

destroyed. The survivors made

an effort to regain their boats, but the five men who had been left in

charge

of them had immediately put off from shore

in

the hindmost boat, and the enemy had already gained possession of the others.

Disappointed in the

attempt, they turned furiously upon the enemy, and,

aided by the approach of darkness, forced their way

through their

lines, and with the loss of several severely wounded, at length effected their escape to Harrodsburgh.

Among the wounded was Capt. Robert

BENHAM. Shortly

after breaking through the enemy’s line he was shot through

both hips, and, the

bones being shattered, he fell to the ground. Fortunately, a large tree

had

Page 742

lately fallen near the spot where he lay,

and with great

pain he dragged himself into the top, and lay concealed among the

branches. The

Indians, eager in pursuit of the others, passed him without notice, and

by

midnight all was quiet. On the following day the Indians returned to

the

battle-ground, in order to strip the dead and take care of the boats.

BENHAM,

although in danger of famishing, permitted them to pass without making

known

his condition, very correctly supposing that his crippled legs would

only

induce them to tomahawk him upon the spot in order to avoid the trouble

of

carrying him to their town. He lay close, therefore, until the evening

of the

second day, when perceiving a raccoon descending a tree near him, he

shot hoping to devise some

means of reaching it,

when he could kindle a fire and make a meal. Scarcely had his gun

cracked,

however, when he heard a human cry, apparently

not

more than fifty yards off. Supposing

it

to be an Indian, he hastily reloaded his gun and remained silent,

expecting the

approach of an enemy.

Presently the same voice was heard

again, but much

nearer. Still BENHAM made no reply, but cocked his gun and sat ready to

fire as

soon as an object appeared. A third halloo was quickly

heard, followed by an exclamation

of

impatience and distress, which convinced BENHAM that the unknown must

be a

Kentuckian. As soon

therefore, as he

heard the expression, “Whoever you

are, for God’s

sake answer me!” he replied with readiness, and

the parties were soon

together. BENHAM, as we have already observed, was

shot through both legs. The

man who now appeared had escaped from the same battle

with both arms broken! Thus each was

enabled to supply what

the other wanted. BENHAM, having the perfect use of his arms, could

load his

gun and kill game with great readiness, while his friend having the use

of his

legs, could kick the game to the spot where BENHAM sat, who was thus

enabled to

cook it. When no wood was

near them, his

companion would rake up brush with his feet, and gradually roll it

within reach

of BENHAM’S hands, who constantly fed his companion and

dressed his wounds as well as his own,

tearing up both of their

shirts for that purpose. They found some difficulty in

procuring water

at first, but BENHAM at length took his own hat, and placing the rim

between

the teeth of his companion, directed him to wade into the Licking, up

to his

neck, and dip the hat into the water by sinking his own head. The man

who could

walk was thus enabled to bring water, by means of his

teeth, which BENHAM could

afterwards dispose of as was necessary.

In a few days they had killed all

the squirrels and

birds within reach, and the man with the broken arms was sent out to

drive game

within gunshot of the spot to which BENHAM was confined. Fortunately,

wild

turkeys were abundant in those woods, and his companion would walk

around and

drive them towards BENHAM, who seldom failed to kill two or three of

each

flock. In this manner they supported themselves for several weeks,

until their

wounds had healed so as to enable them to travel.

They then shifted their quarters, and put up a small shed

at the

mouth of Licking, where they encamped until late in November,

anxiously,

expecting the arrival of some boat, which should convey them to the

falls of

Ohio.

On the 27th of November they

observed a flat boat

moving leisurely down the river. BENHAM hoisted his hat upon a stick

and

hallooed loudly for help. The crew, however,

supposing them to be Indians—at least suspecting

them of an intention to decoy them

ashore—paid no

attention to their signals

of distress, but instantly put over to the opposite

side of the river, and manning every oar, endeavored to pass them as

rapidly as

possible. BENHAM beheld them pass him with a sensation bordering on

despair,

for the place was much frequented by Indians, and the approach of

winter

threatened them with destruction, unless speedily relieved. At length,

after

the boat had passed him nearly half a

mile, he saw a canoe put off from its stern, and

cautiously approached the Kentucky

shore,

evidently reconnoitring

them with great suspicion. He

called loud upon them for assistance, mentioned his name, and made

known his condition. After a long parley, and many evidences of

reluctance on the part of the

crew, the canoe at length touched the shore, and BENHAM and his friend

were

taken on board. Their appearance excited much

suspicion. They were almost

entirely

naked, and their faces were garnished with

six

weeks growth of beard. The one was barely able to hobble

upon crutches,

and the other could manage to feed himself with one of his hands. They were taken to Louisville, where their clothes

(which had been carried off in

the boat which deserted them) were restored to them, and after a few

weeks’

confinement, both were perfectly restored.

BENHAM

afterwards

served in the Northwest throughout

the

whole of the Indian war accompanied the expeditions of Harmar and Wilkinson—shared

in the disaster of St. Clair

and afterwards in the triumph of Wayne.

Lebanon, the county-seat, is pleasantly located in the beautiful Turtle creek valley. The first one hundred lots of the town were surveyed in September, 1802, by Ichabod B. HALSEY, on the lands of Ichabod CORWIN, Ephraim HATHAWAY, Silas HURIN and Samuel MANNING. On the organization of the county, six months later, it was made the seat of justice.

The town was laid out in a forest of lofty trees and a thick undergrowth of spice-bushes. At the time of the survey of the streets, it is believed that there

Page 743

were but two houses on the town-plat. The one first erected was a hewed log-house, built by Ichabod CORWIN in the spring of 1800. It stood near the centre of the town-plat, on the east of Broadway, between Mulberry and Silver streets, and, having been purchased by Ephraim Hathaway, with about ten acres surrounding it, became the first tavern in the place. The courts were held in it during the years 1803 and 1804. This log-house was a substantial one, and stood until about 1826. The town did not grow rapidly the first year. Isaiah MORRIS, afterward of Wilmington, came to the town in June, 1803, three months after it had been made the temporary seat of justice. He says: “The population then consisted of Ephraim HATHAWAY, the tavern-keeper; Collin CAMPBELL, Joshua COLLETT and myself.” This statement, of course, must be understood as referring to the inhabitants of the town-plat only. There were several families residing in the near vicinity, and the Turtle creek valley throughout was perhaps at this time more thickly settled than any other region in the county. The log-house of Ephraim HATHAWAY was not only the first tavern, under the sign of a black horse, and the first place of holding courts, but Isaiah MORIS claims that in it he, as clerk for his uncle, John HUSTON, sold the first goods which were sold in Lebanon. Ephraim HATHAWAY’s tavern had, for a time at least, the sign of a Black Horse. At an early day the proprietor erected the large brick building still standing at the northeast corner of Mulberry and Broadway, where he continued the business. This building was afterward known as the Hardy House.

Samuel MANNING, about 1795, purchased from Benjamin STITES the west half of the section on which the court-house now stands, at one dollar per acre. Henry TAYLOR built the first mill near Lebanon, on Turtle creek, in 1799.

The first school-house was a low, rough log-cabin, put up by the neighbors in a few hours, with no tool but the axe. It stood on the north bank of Turtle creek, not far from where the west boundary of Lebanon now crosses Main street. The first teacher was Francis DUNLEVY, and he opened the first school in the spring of 1798. Some of the boys who attended his school walked a distance of four or five miles. Among the pupils of Francis DUNLEVY were Gov. Thomas CORWIN, Judge George KESLING, Hon. Moses B. CORWIN, A. H. DUNLEVY, William TAYLOR (afterward of Hamilton, Ohio, Matthias CORWIN (afterward clerk of court), Daniel VOORHIS, John SELLERS and Jacob SELLERS.

The

first

lawyer was Joshua COLLETT, afterward Judge of the Supreme Court of

Ohio, who

game to Lebanon in June, 1803. The

first

newspaper was started in 1806 John

McLEAN, afterward

Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court. The

first court-house was a two-story brick

building on Broadway, thirty-six feet square,

erected

in 1805, at a cost of $1,450. The

lower

story was the court-room, and was

paved

with brick twelve inches square and four inches thick.

The proceeds of each alternate lot in the original

town-plat were

donated to aid in the erection of

this

court-house. In this quaint

old building

CORWIN, and McLEAN made

their earliest efforts at the

bar, and Francis DUNLEVY, Joshua COLLETT and Geo. J. SMITH

sat as president judges under the first Constitution of

Ohio. (It

was destroyed by fire

September 1, 1874.) The

Lebanon Academy was built in 1844.

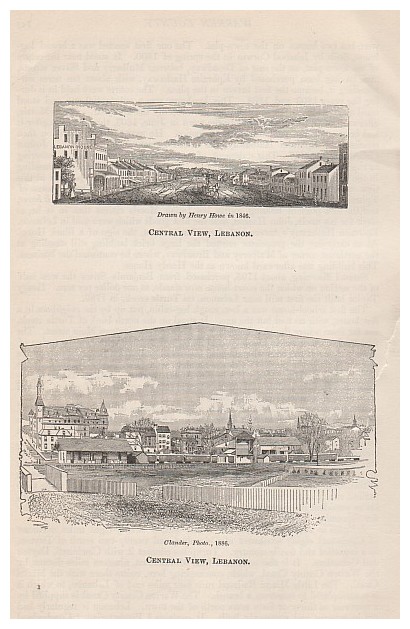

Lebanon in 1846.—Lebanon, the county-seat, is twenty-eight miles northeast of Cincinnati, eighty southwest of Columbus, and twenty-two south of Dayton, in a beautiful and fertile country. Turnpikes connect it with Cincinnati, Dayton and Columbus. It is also connected with Middletown, nineteen miles distant, by the Warren County Canal, which, commencing here, unites there with the Miami Canal. The Little Miami Railroad runs four miles east of Lebanon, to which it is contemplated to construct a branch. The Warren County Canal is supplied by a reservoir of thirty or forty acres north of the town. Lebanon is regularly laid out in squares and compactly built. It contains 1 Presbyterian, 1 Cumberland Presbyterian, 2 Baptist, 1 Episcopal Methodist’ and 1 Protestant Methodist church, 2 printing-offices, 9 dry goods and 6 grocery stores, 1 grist and 2 saw

Page 744

Top

Picture

Drawn

by Henry Howe in

1846.

CENTRAL VIEW, LEBANON.

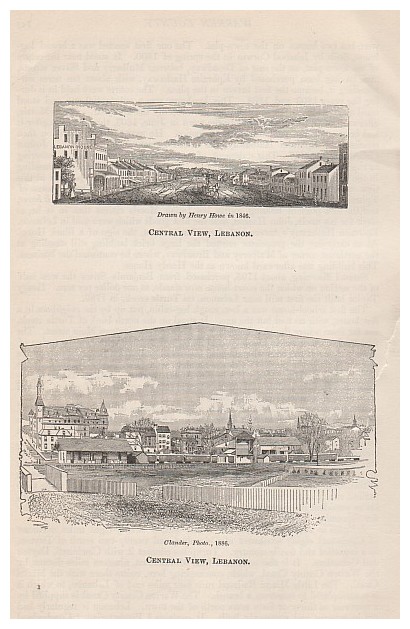

Bottom

Picture

Claunder, Photo, 1886

CENTRAL VIEW, LEBANON.

Page 745

mills, 1 woollen manufactory, a classical academy for both sexes, and had, in 1840, 1,327 inhabitants.—Old Edition.

LEBANON, county-seat of Warren, about seventy miles southeast of Columbus, twenty-nine miles northeast from Cincinnati, on the P. C. & St. L. R. R. It is the seat of the National Normal University.

County Officers, 1888: Auditor, Alfred H. GRAHAM; Clerk, Geo. L. SCHENCK; Commissioners, Nehemiah McKINSEY, Wm. J. COLLETT, James M. KEEVER; Coroner, George W. CAREY; Infirmary Directors, Henry J. GREATHOUSE, Peter D. HATFIELD, Henry K. CAIN; Probate Judge, Frank M. CUNNINGHAM; Prosecuting Attorney, Albert ANDERSON; Recorder, Charles H. EULASS; Sheriff, Al. BRANT; Surveyor, Frank A. BONE; Treasurer, Charles F. COLEMAN. City Officers, 1888: I. N. WALKER, Mayor; S. A. CHAMBERLIN, Clerk; John BOWERS, Marshal; J. M. OGLESBY, Treasurer. Newspapers: Gazette, Republican, R. W. SMITH, editor and publisher; Patriot, Democratic, T. M. PROCTOR, editor and publisher; Western Star, Republican, William C. McCLINTOCK, editor and publisher. Churches: 3 Baptist, 2 Presbyterian, 1 Catholic, 1 Methodist Episcopal, 1 African Methodist Episcopal, 1 German Lutheran. Bank: Lebanon National, John M. HAYNOR, president, Jos. M. OGLESBY, cashier. Has no manufactures. Population, 1880, 2,703. School census, 1888, 853; J. F. LUKENS, school superintendent.

Census, 1890, 3,174.

The National Normal University, of Lebanon, Ohio, Alfred HOLBROOK, president, is an educational institution that has met with a large measure of success. It is conducted as an independent institution, without aid from church or State. It is well equipped with suitable buildings, a fine large library, and an efficient corps of teachers, thirty-five in number. In 1889 the University had 1,940 male and 1,069 female students, and since its founding in 1855 has educated at a very small cost thousands who are now engaged as teachers in professions and in business in all parts of the country.

During the trial at Lebanon, in 1871, of McGEHAN, who was accused of the murder of a man from Hamilton named Myers, the Hon. Clement L. VALLANDIGHAM, who had been retained by the defence, accidentally shot himself. The accident occurred on the evening of June 16, in one of the rooms of the Lebanon House. Mr. VALLANDINGHAM, with pistol in hand, was showing Gov. McBURNEY how Myers might have shot himself, when the pistol was discharged, the ball entering the right side of the abdomen, between the ribs. Mr. VALLANDINGHAM lived through the night and expired the next morning at ten o’clock.

In an old graveyard west of Lebanon were buried many early pioneers. Here are the graves of Judge Francis DUNLEY, Elder Daniel CLARK, Judge Joshua COLLETT, Judge Matthias CORWIN (the father of Gov. CORWIN), and Keziah CORWIN (grandmother of the governor). In this yard was buried a daughter of Henry CLAY, the inscription upon whose tombstone is as follows: “In memory of Eliza H. CLAY, daughter of Henry and Lucretia CLAY, who died on the 11th day of August, 1825, aged twelve years, during a journey from their residence at Lexington, in Kentucky, to Washington City. Cut off in the bloom of a promising life, her parents have erected this monument, consoling themselves with the belief that she now abides in heaven.”

Here lie the remains of four maiden sisters, instantly killed by lightning, as stated on an adjoining page.

Mary Ann KLINGLING, who bequeathed $35,000 to establish the Orphans’ Home, one mile west of town, was buried here, and at her request no tombstone marks her grave. In the Lebanon Cemetery, northwest of the town, are the graves of Gov. CORWIN and Gen. Durbin WARD.

Lebanon is proud as having been the home of Thomas CORWIN. The mansion in which he lived is on its western edge, on the banks of a small stream, Turtle creek, some two rods wide, now the residence of Judge SAGE, of the U. S. District Court, his son-in-law.

Page 746

MONUMENTS IN MEMORY OF FOUR MAIDEN

SISTERS KILLED BY LIGHTNING.

They stand side by side in the old

burial-ground west

of Lebanon. They

lived in a log-house of

four rooms, half a mile west of the town, and each was in a separate

room at

the time of the destructive bold, and all instantly killed.

Page 747

Top

Picture

Clauder, Photo., 1886.

THE CORWIN MANSION.

Bottom

Left

THOMAS CORWIN.

Bottom

Right

Clauder, Photo

THE DOOR-KNOCKER.

Page 748

As I approached the spot not a soul was in sight. I came to the broad door of the mansion, and there faced me a huge brass knocker, on which was engraved THOMAS CORWIN. A quarter of a century has passed, and of all those who have come since and grasped that knocker not one has inquired for Thomas CORWIN. The heart of every one has answered as he read—”dead !” The sight affects as a funeral crape; nay more. It is not only an emotion of melancholy that comes with the sight of that name, but one of sublimity in the comprehension of the character that appears to the vision.

CORWIN was the one single, great brave soul who, on the floor of Congress, dared to warn his countrymen, in words of solemn eloquence, from pursuing “a flagrant, desolating war of conquest” against a half-civilized, feeble race. He implored them “to stay the march of misery.” No glory was to be attained by such a war. “Each chapter,” said he, “we write in Mexican blood may close the volume of our history as a free people.”

To the plea that the war must be continued because we wanted more room, more territory for our increasing population, he replied: “The Senator from Michigan (Mr. Cass) says we will be two hundred millions in a few years, and we want room. If I were a Mexican, I would tell you, ‘Have you not room in, your own country to bury your dead men? If you come into mine, we will greet you with bloody hands, and welcome you to hospitable graves.’ ”

Then he warned them of the inevitable consequences of the war; the acquisition of new Territories; a fratricidal war between the forces of Slavery and the forces of Freedom for the right to enter and possess the land. His closing words were as follows:

Should we prosecute this war

another moment, or expend

one dollar more for the purchase

or

conquest of a single acre of Mexican land, the North and the South are

brought

into collision on a point where neither will yield.

Who can foresee or foretell the result?

Who so bold

or reckless as to look such a

conflict in the face unmoved? I do not envy the heart of him who can

realize

the possibility of such a conflict without emotions too painful to be

endured.

Why then shall we, the representatives of the sovereign States of this

Union—the chosen

guardians of this confederated

Republic—why should we

precipitate this fearful struggle,

by continuing a war the results of which must be to

force us at once upon it?

Sir, rightly considered, THIS is

treason; treason to the Union; treason to the dearest interests,

the loftiest aspirations, the

most cherished hopes of our constituents. It is a crime to risk the

possibility

of such a contest. It is a crime of such infernal hue that every other

in the catalogue of iniquity, when compared

with it,

whitens into virtue.

Oh, Mr. President, it does seem to

me, if hell itself

could yawn and vomit up the fiends that inhabit its penal abodes,

commissioned

to disturb the harmony of the world, and dash the fairest prospect of

happiness

that ever allured the hopes of men, the first step in the consummation

of this diabolical purpose

would be, to light up

the fires of internal war, and plunge the sister States of this Union into the bottomless

gulf of civil strife!

We stand this day on the

crumbling brink of that gulf—we see its bloody eddies wheeling and boiling before us. Shall

we not pause before it be too late?

How plain again is here the path,

I may add, the only way of duty, of prudence, of true patriotism. Let

us

abandon all idea of acquiring further territory,

and

by consequence cease at once to prosecute this war.

Let us call home our armies, and bring them at once within

our

acknowledged limits. Show Mexico that you are sincere when you say that

you

desire nothing by conquest. She has learned that she cannot encounter

you in

war, and if she had not, she is too weak to disturb you here. Tender

her peace,

and, my life on it, she will then accept it. But whether she shall or

not, yon

will have peace without her consent. It is

your

invasion

that has made war; your retreat will

restore peace.

Let us then close forever the

approaches of internal

feud, and so return to the ancient concord, and the old way of national

prosperity and permanent glory. Let us

here, in this

temple consecrated to the Union,

perform

a solemn lustration; let us wash Mexican blood from our hands, and

on these altars, in the

presence of that image of the Father of his country that looks down

upon us,

swear to preserve honorable peace with all the world, and eternal

brotherhood

with each other.

This great solemn appeal of CORWIN full upon dulled sensibilities. The greed of conquest had possession; the popular cry was, “our county, right or wrong.”

Page 749

It brought down upon him a torrent of execration

from

every low gathering of the unthinking, careless multitude.

“To show their hate,”

to use his own words, uttered years later, he was “burned in

effigy often, but

not burned up.” He lived on too high a plane of statesmanship

for their moral

comprehension. All he predicted came to pass. It was as a prophecy of

great

woe. The woe ensued. Half a million of young men, the flower of the

land,

perished; and the Mexican war only ended with the surrender at

Appomattox.

Thenceforward could the old bell on Independence Hall, for the first

time,

truly ring forth, “Liberty throughout all the

land.” No thanks to those who

brought the woe; glory to those who fought for the bright end.

Mr. CORWIN was a great man every way; heavy, strong

in

person, with a large, benevolent, kindly spirit, and an intellect that

illustrated

genius. He was his own complete master; never lost himself in the

crevices of

his own ideas, but could at will summon every quality of his creative

brain,

and bring each to bear as the occasion seemed to demand. Like Lincoln,

a great

humorist, he was at heart a sad man; and his jokes and witticisms were

but used

as a by-play, to relieve a mind filled with the sublimities and

awe-inspiring

questions that ever face humanity.

As his old age approached he thought his life had

been

a failure. Financially, existence had become a struggle; his

aspirations for a

theatre for the exercise of a benevolent statesmanship had been denied,

and he

wrongfully ascribed his failure to his love of humor. That did not in

the case

of Lincoln injure him nor CORWIN, and it never does where a great brain

and a

great soul are at the helm. Then truth often enters through a witticism

when it

is denied to an argument.

On an occasion after observing in a then young

speaker, Donn Piatt, a disposition to joke with a crowd, he said:

“Don’t do it,

my boy. You should remember the crowd always looks up to the ringmaster

and

down on the clown. It resents that which amuses. The clown is the more

clever

fellow of the two, but he is despised. If you would succeed in life you

must be

solemn, solemn as an ass. All the great monuments of earth have been

built over

solemn asses.” CORWIN did not practice as he preached, was

better than his

sermon, and when a witticism demanded utterance put on a lugubrious

face and

out it came. And then it was a joke and its echo, a double dose

bringing

laughter with each, the last laugh by the comical by-play of his

countenance

that invariably succeeded.

Witticisms are immortal. They never die; are

translated. Mark Twain’s Jumping frog, Daniel Webster,

however slow its motion,

may by a century hence have digested his shot and hopped so far as to

appear in

Chinese literature; be a delight to the Pig Tails.

Indeed, a crying demand exists for humor. Chauncey

Depew presents one of his comic creations at a public dinner in New

York, and

the next morning numberless households have it in print at their

breakfast

tables, to help dispel the gloomy vapors of the night and start the

new-born

day in cheerfulness. Therefore, if anybody has anything extra good to

say, it

is their solemn duty to say it, irrespective of their fears of dire

disaster to

themselves for the saying.

It was once my good fortune to hear CORWIN speak in

an

open field to an assemblage of his neighbors and friends, largely

Warren county

farmers; and a jolly, happy set of listeners they were. All knew him,

and, it

was evident, idolized him. Many had taken part in the old Whig campaign

of ‘40,

had helped to make him Governor, had sung:

“Tom Corwin, our true hearts love you;

Ohio has no nobler son,

In worth there’s none

above you.”

And now had come the troubles connected with the

introduction of slavery into Kansas, and it was these he was discussing.

Page 750

In one place he made a comical

appeal for the exercise

of charity in our feelings toward our Southern brethren, that we should

not

cherish bitterness toward them because of slavery. “They were

born into it;

never knew anything else. Think of that? Grown up with the black

people, many

had taken in their earliest nourishment from dusky fountains, kicking

their

little legs while about it,

and it seemed to have

quite agree with them. Then as children they had played together and

had their

child quarrels; sometimes it was young massa

on top and at others pickaninny

on top. Then they

must remember the climate down there was dreadfully hot and enervating.

Nobody

loves to work there. Even some of you fellows up here in old Warren, I

am sorry

to say, seem to shirk work at every chance, and then you hang around

the street

corners and groan ‘hard times.’ This is what makes

it so handy to have some

other fellows around to do it for them—people of about my

color.” CORWIN was of

a dark, swarthy complexion, and it was common for him to allude to

himself as a

black man, and then to pause, stroke his face, and look around upon the

crowd

with a comical expression that brought forth roars of laughter.

“Yes, people around of

about my complexion. when

you want anything done, all you have to do is to yell, ‘Ho

! Sambo,’ and

‘Sambo’

answers, ‘Comin’

Massa,’

and he comes grinning

and does what you order. It may

be you’ve dropped down on a lounge for an after-dinner nap;

on a hot summer

afternoon, your face all oozing a sticky sweat from the close, horrid

heat, and

the flies are bothering you, and one particularly persistent old fly

has lit on

your nose, has travelled

from its starting-place at

the top and finding the bridge a free bridge crossed it without paying

any toll

and is in the opening of the act of tickling your nostrils, gives a

sudden

jab—when it stings; gracious me! Oh

! how it

stings ! It is under that infliction after using, I

fear, some swear words, that you have yelled, ‘Ho! Sambo

ho !’ And then Sambo comes

and he stands and waves over you, gently waves, a

long-handled brush of peacock feathers. It acts like a benign spirit of

the air

with its fanning wings. The flies vanish, the sweat dries, the

locomotive

starts slow—whew! whew!

whew !-then

quick and away you go. You enter an elysium.

Oh, it is very comfortable.

“No wonder our brethren

down there love that sort, of

thing. Their ministers quote Scripture and say it is all right. Paul

comes

along and seems to help them out. Then the owning gives the owner

consequence;

it is a sort of title of nobility. If to own a fine horse puffs up one

of you

folks up here, think how big you would feel to own a man a cash article

always

at hand when one’s hard up—pickaninny

$250, an old

aunty $500, and a Sambo

$1,000, that is if the

preliminary examination of Sambo’s

teeth and gums

shows he has not aged too much. And now the question arises about

allowing

these Southern brethren of ours to take along to the new lands which

their arms

have helped to obtain, their Sambos,

old black nurses

and pickaninnies, so as

to keep up the old style of

family arrangements. It is a very troublesome question to discuss, but

we must

do it in all charity.”

These were not his words nor illustrations, but about their spirit, as in my memory—the by-play of an earnest, judicial talk upon the great trouble that was setting the people North and South at loggerheads “ “befo” de wah.”

.

. .

. . .

. .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

.

An old-style door-knocker hanging from the door of an old family mansion ! hat a sense of dignity it confers upon the spot, and what a history it could give if it could talk and tell of those who have come, the young and old, the rich and poor, and of their varied errands of sociality or business;’ if socially, what sort of a time they had; if business, were they duns?

The very act of knocking is a prayer, a petition to enter; and with it are .two mysteries: “Who is that knocking at my door?” that is the inner mystery. “Who will answer my knock ?” that is the outer mystery. The echo of your own knock has come to you, so you know somebody must have heard it. The family may be away, and the only answer you get is, perhaps, from a little creature in the hallway who has flown up just behind the door, scratches it and gives a “bow-wow.” Noah had no door-knocker to his mansion; nor did our Buckeye pioneers. Their latch-strings were always out, it was but a pull and then came open hospitality. “Hospitality,” said Talleyrand, “is a savage virtue,” and the pioneers had it, too.

The door-knocker was a direct evolution from the earliest origin—knuckles—and now comes the button for a shove and its answering ting-a-ling.

.

. .

. . .

. .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

.

When I lifted the old brass knocker, “Thomas Corwin,” I felt it an honor;